My Life in Rags

From Costumes to Quilts

by Eleanor Knowles Dugan

Lots of people laugh. “Why,” they ask, “do you take a big piece of cloth, cut it up into little pieces, and then sew them back into big pieces again?”

It’s a reasonable question. The art and craft of quilting has progressed from a survival skill of the struggling to a pastime for the leisured and even, occasionally, an art form. Why do we still resort to the meticulous piecework developed by our forbearers back when a yard of machine-woven cloth cost a week’s wages, and every scrap must be used?

Today’s quilters have almost unlimited fabrics and fibers to work with, but we still insist on reducing the whole to smaller elements, then reconstructing our personal vision of color, texture, and density. You might as well ask painters why they open their paint tubes when the colors are already so neatly sorted out. Or ask the mason or the carpenter why they break up one whole to create another. It is essential to creativity, a basic human need to alter our environment on a large or small scale.

Twelfth Night for Theatre in Education, New York City, 1963

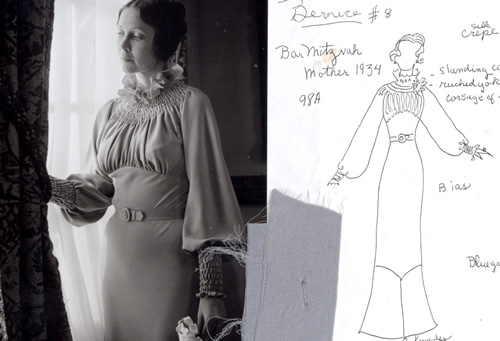

I came to quilting after many years as a stage costumer, accustomed to combining a myriad of fabrics, colors, and textures into a whole. A stage costume has some advantages over a quilt as a work of art. It is literally stage center in the spotlight, demanding attention, powerfully supported by the drama of the moment and the movement and actions of the wearer. It has context and immediacy.

Designing a stage costume is a collaboration, rather like being an architect. The design must fit in the whole production and allow for such things as quick changes, body mikes, and choreography. It must please both the director and the actor–and often extraneou bystanders. Even when budgets are large enough to cover fine materials and skilled construction people, costumes are always built on ridiculously tight schedules. The designer walks a perilous course between integrity, expediency, and compromise until the finished costume appears before an audience. Costumes are a fugitive art. Like the performance they support, they are specific to a moment and age rapidly, rarely surviving more than a few months, sometimes only a few weeks before they must be replaced.

Lepke, 1975. Anjanette Comer

When I turned from costuming to child raising, I decided that quilting might offer an even more satisfying medium–a chance to be absolute boss, to control all the elements of design without the frustration of collaboration. The intense tactile satisfaction of working with fabric is the same, the almost sinful fulfillment of soft, rough, smooth against the fingers.

There’s the delight of collecting and combining the mundane and the tasteless—the polyester daisy print, some white-on-white shirting, pajama flannel, op and pop and slop art fabrics—with fragments of your own clothing. As with Prospero’s “sea change,” the tiny bits become “something rich and strange,” losing their identities as they mutate into a glowing and subtle tapestry.

Yet there are drawbacks to quilting too. Compared to the union wages of a costumer, a quilter’s income (if she can bear to sell anything) is diddlysquat. Fibers are still fragile. Few quilts survive beyond their owner’s lifetime, and then rarely another hundred years. Quilting is still considered a craft, not an art. Interest in quilts is cyclical, like hula hoops and canasta. Decorator magazines routinely show old quilts lying on floors or used as tablecloths on picnic tables heavy with juicy watermelon slices and dripping barbecue. Even wall quilts by recognized artists are really just commercial art. They are bought with a preordained percentage of the corporate budget and used to “humanize” a blank office space until soil, fluorescent lighting, and neglect take their toll.

Autumn Pond, 1986, 36″ x 60″

My first quilts went on beds where quilts are supposed to go, a logical extension of the sensuality of the creative process. Puppies’ claws, upset tummys, and Hawaiian Punch quickly aged them into retirement. The wall was my next site, remote from many daily disasters, but also from the direct contact that makes fabric so personal. But, I comforted myself, tapestries and carpets evolved to cover walls, to keep out the cold while providing warmth for the eye and the spirit.

I sort my colors. Somewhere in the pile may be just the right gray-green to support one end of the amber bar as it emerges from the field of plum and gray diamonds. Helpful friends look at my latest effort and ask, “Where are you going to hang it?” There is nowhere to put it. It exists, not to fill a space on my wall, but a space in my heart.

They say encouragingly, “Why don’t you make a Gone with the Wind quilt?” or “a Wizard of Oz quilt?” I smile and nod and go back to my triangles and parallelograms. Speak to me rather of 72-degree angles and Wang dominoes, of nonrepeating tessellations. My palette and patterns are nearly limitless, my inspiration extended by computer graphics, my medium as old as the first creature who gathered vines to use as ropes. I have moved my rags from the spotlight to a private place where few others look with my eyes. But the vision is all mine.